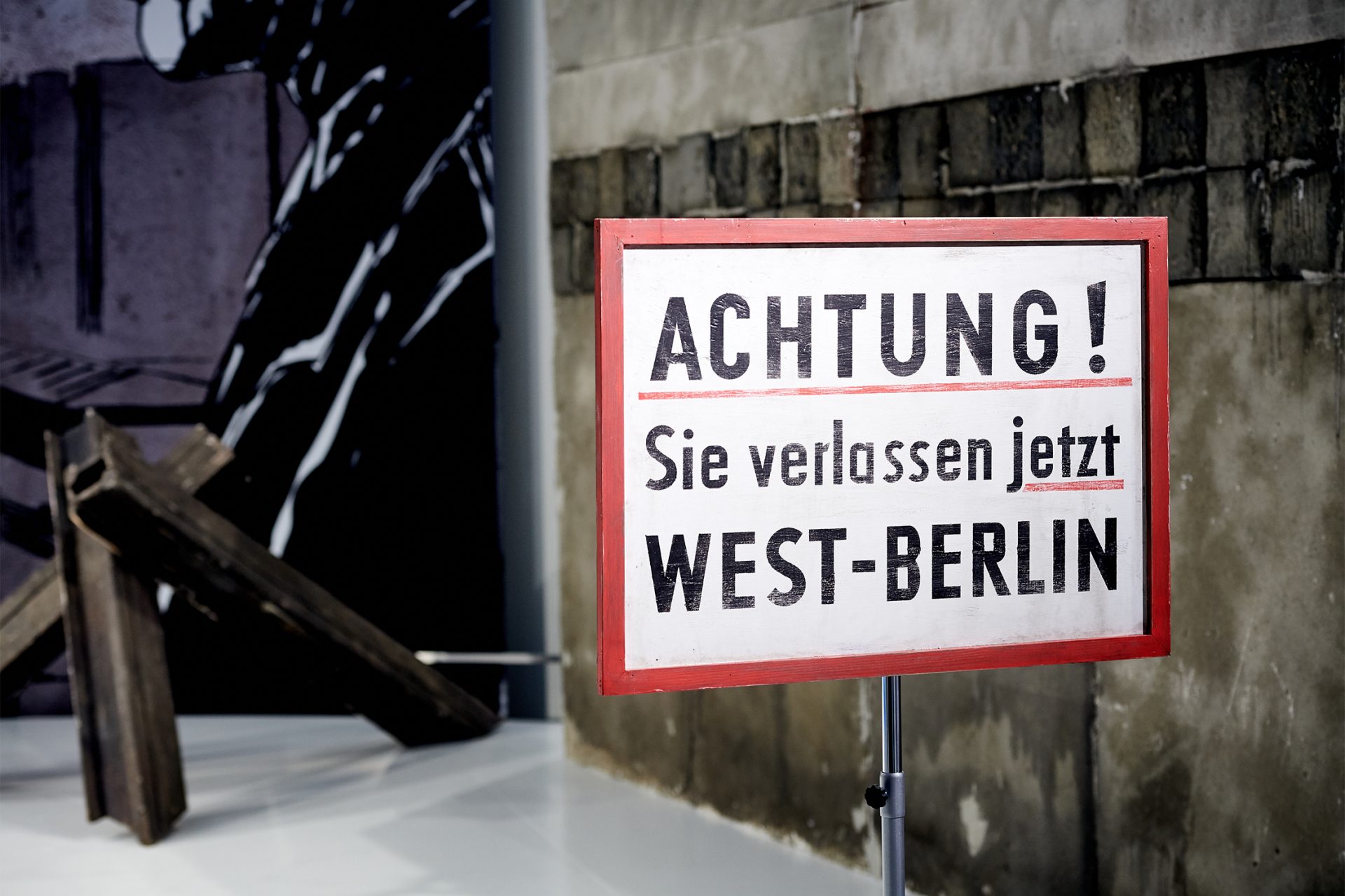

The year is 1963: the border to East Germany is closed and the Iron Curtain has descended with a merciless thud. Berlin is a divided city, its western and eastern zones eying one another with unflinching suspicion. Any attempt to leave East Berlin now means risking life and limb. Escape artists devise one new method after another – digging tunnels, scrambling improvised aircraft and, of course, modifying all manner of vehicles to whisk away the new band of refugees. But nobody had thought of using a BMW Isetta; how, after all, could you hide anyone within its miniscule frame? Klaus-Günter Jacobi found a way, handing his childhood friend a passport to the freedom for which he yearned. This adventure at the meeting point between the two Germanys would write its own chapter in history.

Klaus-Günter Jacobi was living in West Berlin when a childhood friend approached him with a plea. Manfred Koster implored Jacobi to help him flee East Germany, by now completely sealed off from the West. Time was of the essence, as Koster had been drafted to the army and couldn’t afford to hang around.

Escaping the clutches of the Iron Curtain called for extraordinary cunning. An order to shoot was in force at the border fences and guards carried out meticulous checks at the crossings. Cars were subject to particularly rigorous searches. Klaus-Günter Jacobi needed an idea nobody had thought of before. Enter the Isetta – all 2.30 m (length) and 1.40 m (width) of it – which Jacobi had been the proud owner of for some time. The notion of using the jaunty “bubble car” as an escape vehicle seemed absurd, but maybe this would also make it perfect for the job at hand.